Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

Human Lunar Return

Human Lunar Return

Credit: NASA

Status: Study 1996.

The final Human Lunar Return study of 1996 was the ultimate cut-rate fasterbettercheaper manned lunar mission - requiring only two shuttle and three Proton launches, and landing two crew at Aristarchus in an open-cab lander. Total cost $2.5 billion; total time to achieve, five years. The collapse of the fasterbettercheaper approach and renewed public and NASA interest in Mars resulted in HLR sinking from sight...

NASA Administrator Dan Goldin initiated the "Human Lunar Return" (HLR) study in September 1995 to investigate innovative fast-track approaches for manned spaceflight. HLR thus tried to apply the same philosophy as the X-38 Assured Crew Return Vehicle Experimental (ACRV-X) project and Discovery class of "cheaperfasterbetter" unmanned planetary probes. ACRV-X was regarded as an important pathfinder since it was developed in-house at NASA's Johnson Space Center by a small team, and much of the software was going to be reused for Human Lunar Return as well.

The HLR's fast-paced program schedule and goals were very ambitious: a human lunar return by 2001 and expanded lunar and Mars activity beyond 2001. To achieve this goal, the Human Lunar Return project would have to demonstrate technologies for orders of magnitude reduction in cost to allow eventual commercialization of lunar resources and extended lunar operations in 2005 and on. These two elements (2001 Human Lunar Return, commercial lunar ops. by 2005) would consume the lion's share of the funding. NASA estimated that the total cost through 2005 would be about $4 billion, excluding launch costs (the project would have required 11 large Titan-IV class launch vehicles, 2 Delta II class LVs and one Taurus-class launch up to the first manned lunar landing). NASA and its traditional, experienced partners would primarily fund and run the 2001 mission, but "non-traditional" commercial partners and international agencies would be expected to play a bigger part in the post-2001 effort. NASA would then provide expertise but only limited direct funding. Like most lunar initiatives during the Goldin era, the main long term HLR objectives were commercial in-situ resource development and demonstration of manned Mars mission technologies on the Moon.

The new HLR "vision" called for opening a "pipeline" of small-scale "skunk works" experimental unmanned projects and manned missions, which quickly and independently would demonstrate enough progress to justify additional investment. The ideas in the pipeline would be tested through three or four simultaneous X-projects (which might be ground tests, tests in low Earth orbit or lunar tests) at acceptable cost (<$100M per project) and risk. NASA's role was to prioritize the ideas entering the pipeline, utilize its unique capabilities to move ideas through the pipeline, and work with commercial and international partners to make the pipeline as wide as possible. The manned X-mission follow-ons would use available Shuttle/ISS infrastructure and manpower to the fullest extent possible. Additional government and private investments would then turn the experimental technologies into NASA operational capabilities and/or commercial operations supporting lunar and Mars exploration and utilization. The HLR team felt this would eliminate the enormous investment required to achieve an initial "X-Mission" lunar operating capability. As desirable as the previous approach might have been for avoiding the fate of Apollo, the initial investment of previous initiative had always proved too high for the lunar outpost to become politically realistic. The four demonstrators were:

- "Transtage-X1". This low-cost technology demonstrator was identified for launch in 1998-2000. In many ways, the X-projects were going to continue from where President Reagan's aborted Pathfinder program left off in 1988. The subscale vehicle would perform a circumlunar flyby and then brake into a circular low Earth orbit using a circular aerobrake heat shield. Costs would be minimized by utilizing an existing solid propellant rocket stage (STAR-63) and existing hardware from the cancelled Aeroassist Flight Experiment (AFE) and ACRV-X avionics. The vehicle would be deployed from the Space Shuttle in 1998. A modified "Transtage-X2" version might later be used to demonstrate in-flight cryogenic propellant transfer in 1999 and assembly of a full-scale aerobrake for future Transtages capable of ferrying astronauts to lunar or geostationary orbit starting in the year 2000.

- "Cryosat-X1". The second cornerstone X-mission was to demonstrate the storage and transfer of liquid oxygen and hydrogen propellant in low Earth orbit. NASA's HLR architecture would eventually require a propellant depot stationed at a Russian FGB space tug from the International Space Station program. The FGB was favored since it would offer international participation and application of ISS components without disturbing microgravity experiments on the Space Station. It would be launched on a Proton booster in 1999. The required zero-G propellant transfer technologies could be demonstrated on a Taurus rocket flight to low Earth orbit in 1998. The Cryosat-X1 mission would deliver small amounts of propellant in Space Shuttle PRSD tanks, to the FGB depot. ACRV-X components might also be used on this mission.

- The "Mission X" project would demonstrate automated, safe and accurate lunar landings using a subscale robotic lander vehicle launched on a Delta II or Titan 2 booster in 1999. The design might later be used on a second mission in 2000 for deploying navigation beacons and lunar oxygen extraction experiments on the future site of the first manned lunar landing. Finally, a larger crewed version would be required for both endo- and exoatmospheric crew training and for design, test and verification of the operational manned lunar lander. Commercial off-the-shelf avionics from ACRV-X, DC-X and the AV-8B VTOL aircraft as well as new virtual reality teleoperation technologies might possibly be utilized on the vehicles.

- The "X-Suit" project would try to develop a low-cost ($10,000-$100,000/suit) alternative to the existing Shuttle EVA space suit which costs $20 million per copy. Requirements include: mobility for lunar exploration, dust protection, field servicing capability, compatibility with lunar vehicle & mission objectives and light weight. The options investigated in 1996 were a 95kg hybrid soft/hardsuit with an integral life support backpack, and a 75kg "soft" suit with a Space Shuttle helmet. Both would be significantly more capable than the Shuttle's 125-kg EMU spacesuit, which did not have movable legs and therefore was unsuitable for lunar exploration.

The preferred Human Lunar Return "Architecture B" option was surprisingly similar to NASA's (horrendously expensive-) "90-Day" Space Exploration Initiative plan from 1989. The space-based reusable "Transtage" space transfer vehicle would deliver the manned lunar vehicle to a low lunar orbit. The manned vehicle would now consist of an orbiting Earth return vehicle (ERV) and a lander which descended to the lunar surface with the astronauts. The astronauts would return to the waiting ERV mother ship in lunar orbit after a 2-week surface exploration mission. The spent lander would be jettisoned and the Earth return vehicle would return to the crew to low Earth orbit. This architecture would contain the same elements as HLR Architecture A, with the addition of a large aerobrake for the reusable Earth return vehicle. The Architecture B scenario would run as follows:

- The Transtage + Earth return vehicle would be launched in 2000 and assembled at the FGB-derived propellant depot;

- The manned lunar vehicle + crew would be launched to the International Space Station (ISS) in 2000. The Transtage, Earth return vehicle + Crew Module were all fully reusable so they did not have to be replaced (for subsequent missions, a single Shuttle launch would deliver a replacement lunar lander + logistics to ISS);

- After checking out the vehicle, the astronauts would move their spacecraft to the FGB propellant depot;

- A modified X-38 Assured Crew Return Vehicle would be normally used for in-orbit traffic between the FGB depot and ISS;

- The propellant (which was delivered on four separate Proton or Ariane-5 launches in 2000-2001) would be transferred to the lunar vehicle;

- The lunar stack would depart from the FGB fuel depot in early 2001.

- In the return sequence, the Transtage TLI vehicle and manned Earth return vehicle both aerobrake into low Earth orbit and dock at the FGB depot, where they were serviced and refueled for future missions. The crew transfers to ISS in the same Crew Module that provided housing and life support during the lunar trip.

HLR would have to rely on existing launchers such as the Proton and Ariane-5 since the cost of building a new heavy-lift rocket was deemed too high. The propellant packages would be compatible with all spacefaring nations' major launchers and the interfaces would be simple. But the cost would still be high since 80% of the total mass in low Earth orbit was propellant, and a minimum of four Proton/Ariane-5 class launches would be required per lunar landing. On the other hand, the Proton or Ariane-5 would not require an expensive GEO upper stage or payload insurance since the payload itself (oxygen/hydrogen propellant tanks) would be inexpensive. Therefore, the cost of a Proton delivery might be less than the $50-75M price charged by International Launch Services for a commercial GEO launch. The HLR planners thus felt a 1920s Air Mail type private propellant delivery service would make a great deal of sense. Economies of scale might be possible since the manned lunar program would require eight launches per year in 2002. It was also hoped that barter deals and cost sharing among the international space station partners would reduce the cost to American taxpayers.

The Architecture B launch schedule ran as follows:

- 1998: Transtage-X1; Cryosat-X1 = (1 Proton or Ariane 5 Launch; 1 Taurus Launch)

- 1999: Lunar Experiments; Transtage-X2; FGB Propellant Depot (Cryosat-X2) (2 Proton or Ariane 5 Launches; 1 Delta 2 Launch)

- 2000: Transtage; FGB Tug; + 2 Propellant launches; Lunar Landing Beacons (4 Proton or Ariane 5 Launches; 1 Delta 2 Launch)

- 2001: Lunar Lander; Crew Module; 2 Propellant launches (4 Proton or Ariane 5 Launches)

By June 1996 Architecture C consisted of a Lunar Orbit Stage (formerly known as Transtage) and packaged lunar landing vehicle delivered in the Space Shuttle cargo bay. The Lunar Orbit Stage was protected by a 9.144-meter diameter aeroshell, which would be launched in seven segments to save space. The aeroshell was assembled before rendezvous with ISS and then moored to the Space Station. A second Shuttle flight delivered the crew and propellant for the lunar vehicles. The refueling operations were simplified since the LOS and LLV utilized storable hypergolic propellants, which required no new propellant transfer technologies. The 15.6-metric ton LOS vehicle only carried enough propellant for lunar orbit insertion and trans-Earth injection; two expendable 20-metric ton propulsion modules (derived from the Russian "Breeze" upper stage and launched on two Proton rockets) performed the translunar injection burn. The LOS carried a small unpressurized Lunar Landing Vehicle and a 2.5 meter long Command Module capable of supporting two astronauts for up to 19 days during the Earth-Moon transfer. Date of departure from ISS: August 24, 2001.

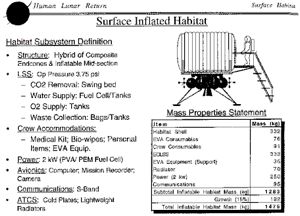

To save mass, the HLR would use an unpressurized open-cockpit Lunar Landing Vehicle weighing just 4,565 kg with fuel. The vehicle was 3.9 meters tall and 5.6 meters wide. The space-suited crew of two received oxygen and other life support consumables via umbilicals from the LLV. The HLR crew would live in an inflatable 2.5-meter diameter x 3 m long Surface Habitat, which would be delivered in advance to the lunar outpost site at Aristarchus (26.4 deg. N, 44.1 deg. W) by an unmanned Proton rocket on August 1, 2001. The hab lander and Lunar Landing Vehicle would share a common basic design. The habitat was powered by a 4.1-meter diameter round solar array. It had a mass of 1,475 kg on the lunar surface plus 300 kg of science payload. The crew arrived on August 31 2001 and departed three days later. After jettisoning the LLV in lunar orbit, the LOS performed a three-burn trans-Earth injection, aerobraked in Earth's atmosphere four days later and entered low Earth orbit where it docked with the International Space Station on September 9, 2001. The total cost of the first manned landing would be $2.5 billion. Each mission required two Shuttle flights and three Proton launches to deliver the lunar habitat, LLV, LOS, propellants and TLI stages.

The first mission would be followed by three identical 3-day lunar sorties in 2002-2004 and an unmanned mission to the lunar south pole. In 2004, a rover and a lunar oxygen plan capable of producing 2.2t of LOX per year would become available. A site for a semipermanent lunar outpost would be identified at this point. In 2005, two crews (mission #5 and #6) would spend 14 days in a reusable multiple habitat connected by an inflatable airlock; the astronauts would be supported by reusable LLVs and a Lunar Orbit Stage equipped with two Command Modules. By 2006, a full-scale LOX plan would produce 20t of oxygen per year. A larger 4-6 man "Block 3" habitat and pressurized long-range rover would become available in 2007-08. The Human Lunar Return would thus gradually evolve towards the same capabilities as NASA's "Space Exploration Initiative" lunar outpost from 1989.

NASA's Human Lunar Return project was quietly shelved in late 1996 as the agency's lunar efforts were totally eclipsed by exciting news from Mars. On the same day as the final HLR briefing on August 7 1996, NASA/Johnson scientist David McKay announced officially that his team had found evidence of ancient life in a meteorite from Mars. The triumphant landing of the unmanned Mars Pathfinder in 1997 further overshadowed the fading lunar effort. Nonetheless, the Human Lunar Return study was able to make substantial progress although the timing was highly unfortunate. A manned lunar return by 2001 always seemed unlikely due to the agency's financial problems with the International Space Station. Dan Goldin's "cheaper-faster-better" approach also turned to be relatively ineffective in the fields of manned spaceflight and future space transportation -- the estimated cost of ISS grew from $17 billion to $30 billion and the X-33, X-34 experimental launch vehicle programs also exceeded their budget before they were cancelled in 2001. In the light of this, the HLR team's "X-project" cost estimates from late 1995 seem highly optimistic.

In 1996, Human Lunar Return focused on bare-bones manned lunar architectures that perhaps did not provide as many benefits as previous, more expensive proposals and the risks of a "poor man's Apollo" may have seemed prohibitively high. But it seems increasingly clear that NASA's post-ISS projects would have to be significantly less expensive and based on new commercial "paradigms" as well as international participation. In this respect, the groundwork provided by HLR may prove invaluable in the long term.

Family: Lunar Bases, Moon. Country: USA. Agency: NASA.

| Human Lunar Return Credit: NASA |

| Human Lunar Return Credit: NASA |

Back to top of page

Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

© 1997-2019 Mark Wade - Contact

© / Conditions for Use